Typographic glyphs have their moments. The @ symbol was barely used before it became indispensable for email and social media. The creation of the single European currency saw thousands of fonts being reissued to include € at the turn of the century. It’s likely that some crypto-boosters are hoping this will happen again, and the double-barred B of Bitcoin will become de rigueur in fonts. Sometimes new forms arrive more surreptitiously.

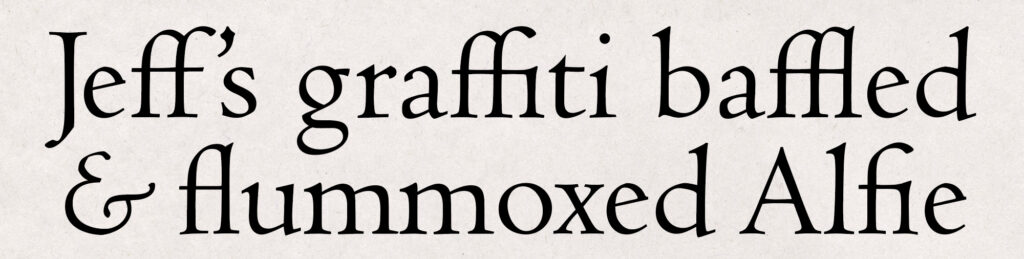

In digital versions of Latin alphabet fonts ligatures, or ligs, the neat typographical devices which combine two or more characters into a single glyph, fall into two classes. Standard ligatures – usually ff, ffi, ffl, fi and fl – solve the problem of the overhanging hook of the lowercase f by tidily combining it with the following letter. Discretionary ligatures such as st and ct, based on once-common historical models, can look antiquated, hence a pre-digital name for them: quaints. The unobtrusive standard ligatures are now a feature of most old-face (serifed) fonts. The more conspicuous discretionary ones are rarely used in body text in modern typesetting, most often being reserved for ads, book jackets, headings, title pages: places where there is the reason and space for decorative flourishes, and where brisk continuous reading isn’t a consideration.

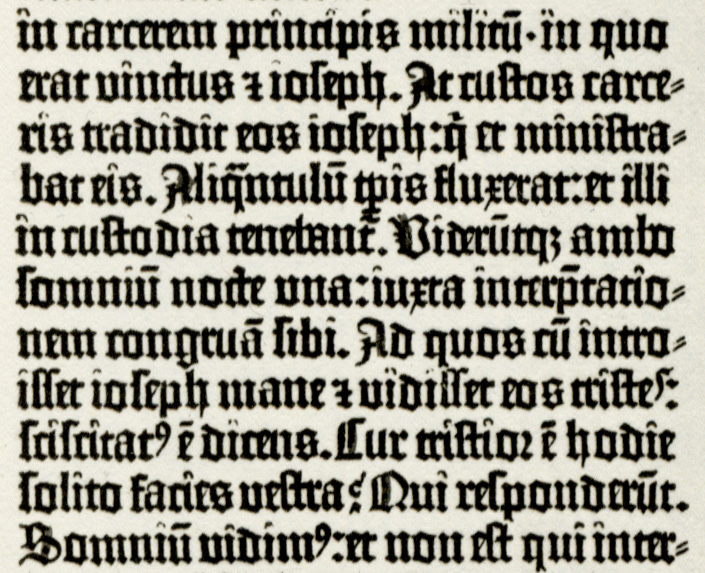

As constituents of the typecase ligatures were subject to a long diminishment over the centuries. Blackletter fonts, the earliest form of moveable type in Europe, usually included dozens of them. Gutenberg’s Bible had more than fifty, although the type is so tightly fit it’s sometimes difficult to distinguish them from individually cast letters.

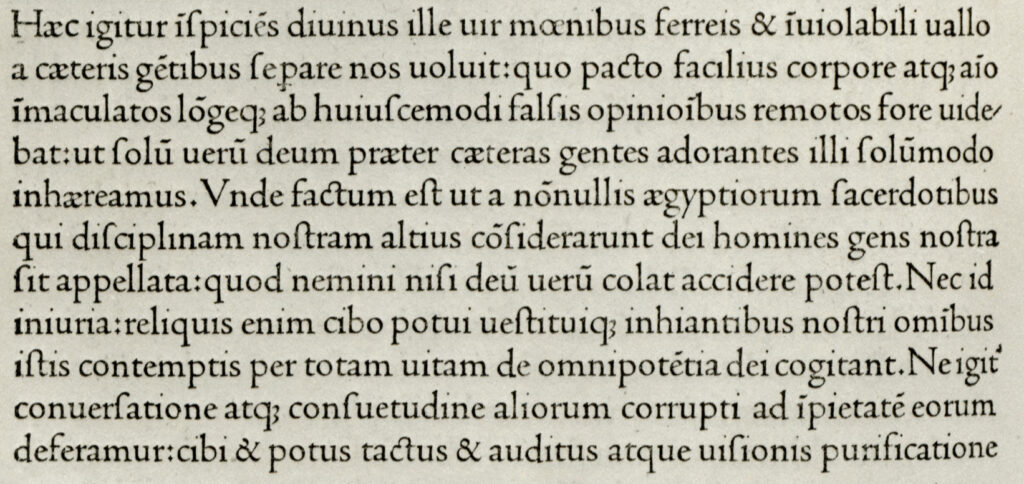

There were fewer in the looser-fit roman and italic fonts that came later in the fifteenth century, and fewer still when manual composition of type was practically superseded by hot metal setting at the end of the nineteenth century. From the middle years of the twentieth century, in many of the fonts made for photocomposition they had all but disappeared. Unconstrained by the physical restrictions of cast metal, this was when it became possible, if unadvisable, to plonk bits of one character over parts of another.

Ligatures were absent from the limited character sets of the very earliest digital type which arrived at the beginning of the 1980s. (Italics were sometimes missing too, these being poorly mimicked by the roman font given an oblique slant.) But by the end of the decade most commercial fonts, or at least ones which a designer might be willing to pay for, had reinstated the standard ligs.

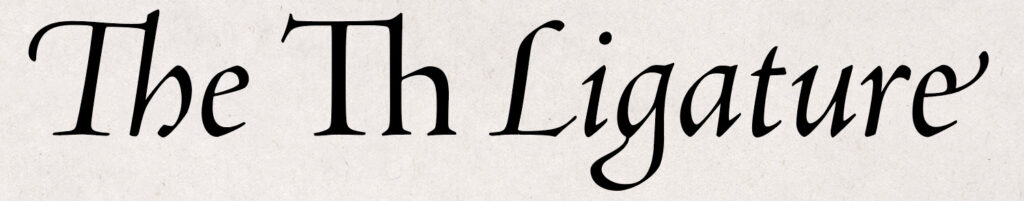

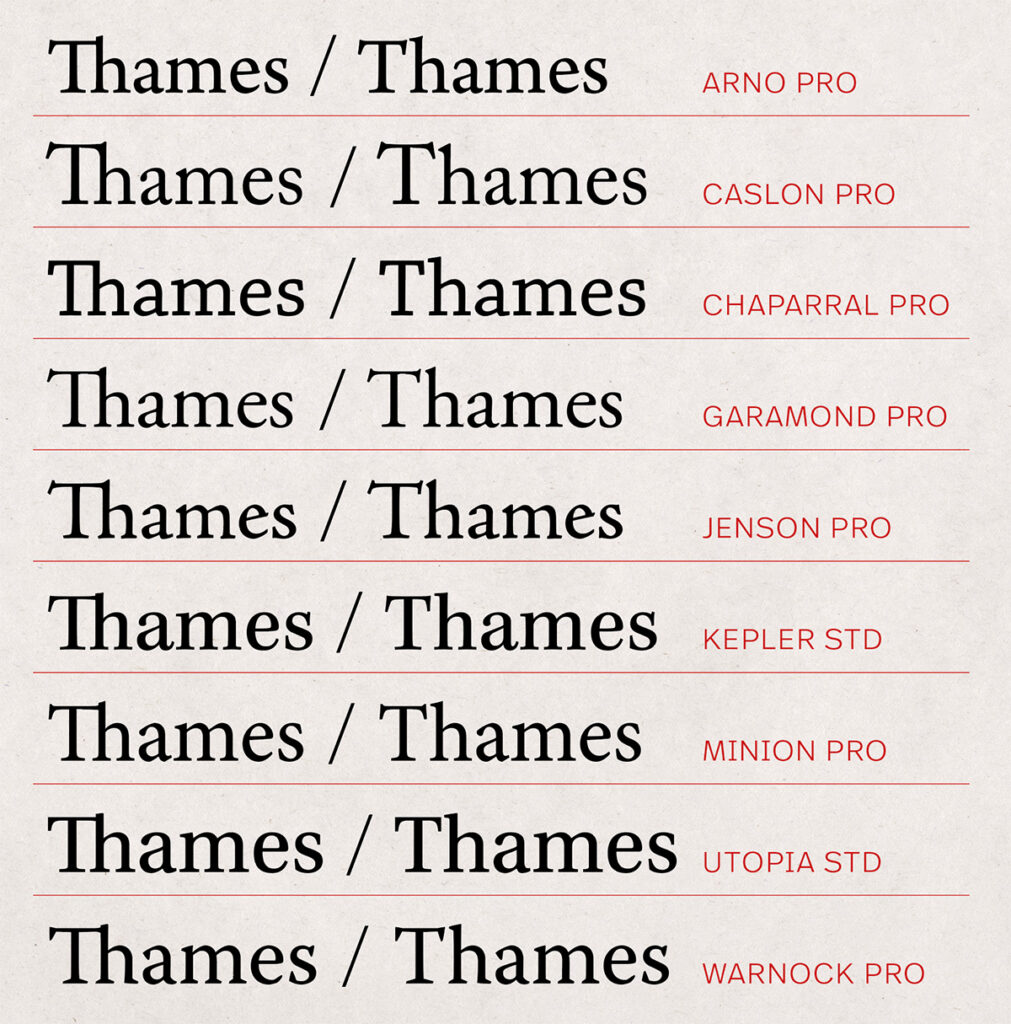

In this century another yoked couple has made a stealthy arrival and has become surprisingly common. The Th ligature now turns up in the web fonts used by, among many others, the Atlantic, McSweeney’s, LitHub, and restofworld. Over the past few of years I have come across it in more and more of books, and I have a firmly divided opinion about it. When used in large sizes, as in the illustration below, or for titles and short strings of text, there is no reason for a designer not to use it if they see fit. In anything meant for continuous, sustained reading – in the body text of articles and books – it should always be avoided.

For the most part, it is an anglophone issue. An uppercase T followed by a lowercase h is a rare combination in most Latin scripts. It barely appears in romance languages, and isn’t much more common in most other lexicons. But in English it’s all over the place. The confounding multiplicity of Thomases in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall; every Thursday; This and That, These and Those; and the word most frequently used to start a sentence in the language: The.

The form isn’t necessarily a novelty – most commonly paired letters have been seen hitched in manuscript, inscription and print for centuries – but historically, in moveable type which was originated for the setting of text in Latin where the combination barely exists, it has been rare. What is definitely new is how some type designers are designating the glyph in digital fonts: not among the discretionary ligatures, where it surely belongs with the quaints, but with the standard ones. (There is no standard in the sense of a protocol agreed among type designers: each foundry decides for itself what’s discretionary and what’s standard.)

Typefaces which have been fitted with the Th lig as standard have been introduced by several designers and foundries over recent years, including Alegreya by Juan Pablo del Peral, Cormorant Garamond by Christian Thalmann, and GT Sectra from Grilli Type. But the momentum behind the glyph’s new pervasiveness certainly has one primary driver: Adobe Systems. It’s arguable that no company has had a greater influence on the development of digital typography than Adobe, creator of the PostScript page description language and the ubiquitous PDF. From the late 1980s the firm also started issuing its own type under the Adobe Originals brand. Among these are popular revivals of renaissance and enlightenment typefaces, including modern interpretations of type made by Nicolas Jenson, Claude Garamond and William Caslon. These, and several other Adobe faces, have now been retrofitted with the anachronistic Th lig. Even if one doesn’t like the thing, it’s easy to understand why these fonts are so widely used. They have extensive character sets including rarely used (but for some work essential) characters and diacritics. And if one signs up to any of Adobe’s graphics products – including InDesign, the most widely used page-layout program for professional publishing – as well as the app, the subscription includes access to these and thousands of other fonts as part of the deal, with no additional licensing costs.

Obviously some type designers are fond of the thing: no one asked for it, but there it is. Perhaps a few graphic designers and typographers find it delightful too, and wonder why it took so long for it to gain favour. But T and h in their distinct forms have sat next to one another harmoniously for centuries. The space between the letters isn’t an aberration to be eliminated: white space is integral to the design of words on pages – we don’t focus just on perfected letterforms, we read the paper and the ink together. Although it is possible, if more awkward than it ought to be, to omit the pairing without also losing the rest of the standard ligs, it seems to have been lazily accepted. Or perhaps it’s simply invisible to most people, and only cranks are vexed by it. I don’t have a particularly well-adapted eye for distinguishing one typeface from another, but whatever the font, the Th lig pulls my attention from the text to the form of the text every time it appears. It isn’t irritating in the way of a background-noise which after a while one can become accustomed to, it’s more like a smoke detector with a failing battery: a faint yet shrill chirp, inexorably chiming just as one has forgotten to expect it.

¶ Images. The details from the 42-line Bible and De Evangelica Praeparatione are taken from Art of the Printed Book (Pierpont Morgan Library, 1973). Images included in this post may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license.